About

Goals & Objectives

Elements

Research & Public Engagement

Environment Report

Kenton County is rich in natural resources such as fertile soil, forestland and valuable water resources that provide many essential benefits. The ability to integrate the natural and built environment will be crucial to supporting a safe, healthy, and sustainable community. This report will establish the current condition of natural resources and services including the current state of Northern Kentucky’s watersheds and receiving streams. An environmental profile of Kenton County’s natural features reveals that the land is made up of steep hillsides and heavily wooded deciduous forests. Kenton County is a part of the Ohio River Regional watershed. Due to soil composition, terrain, and the growing population within the Greater Cincinnati Metro Region; Kenton County often experiences areas of flooding, landslides, deforestation, and other environmental issues. It is important to understand the need to balance opportunities for development while protecting natural features for the environmental health of Kenton County.

A watershed is the land water flows across or through on its way to a common receiving water, such as a stream, river, lake, or ocean. Watershed boundaries are established along the tops of ridges and hills and determine what direction runoff from rain will travel once it hits the surface. Changes in elevation, the geologic formations and terrain dictate where and how water will flow in a given area. Examining the physical structure of the county in relation to established boundaries, such as ridge tops and stream valleys, provides an understanding beyond man-made jurisdictional/political boundaries. Using this concept one can begin to identify basic sections of land draining into a watershed.

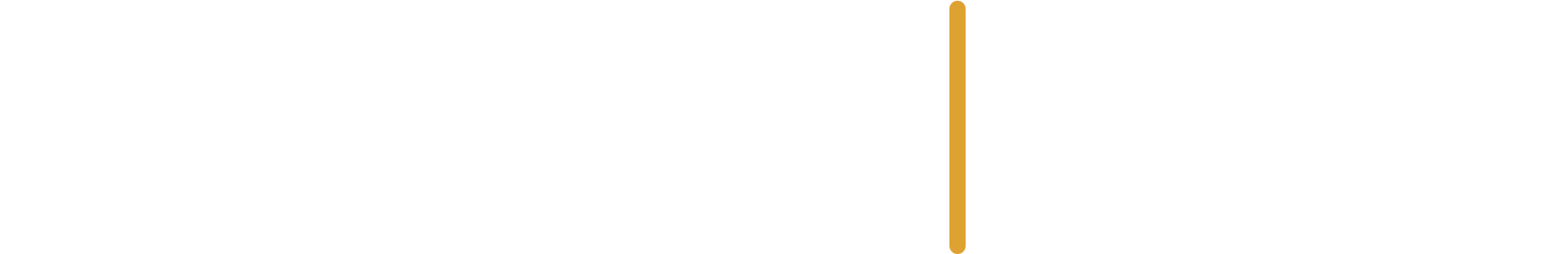

In Kenton County, watersheds are monitored by Sanitation District No. 1 (SD1). As shown in Figure 1, SD1 manages Northern Kentucky’s wastewater and storm water throughout 16 delineated major watersheds across Boone, Campbell and Kenton Counties as shown in Figure 1.

Four of these watersheds cover the majority of Kenton County and are monitored and managed through SD1’s Watershed Assessment Program. This assessment program includes in-stream water quality and biological monitoring of several hundred miles of streams that drain over 500 square miles of land 162 square miles of which is in Kenton County.

SD1 is responsible for the collection and treatment of wastewater and regional storm water management throughout the Northern Kentucky region. SD1 is also responsible for reporting to and adhering to guidelines and regulations mandated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). SD1 has negotiated an agreement with the EPA and the Kentucky Energy and Environmental Cabinet to address sanitary sewer overflows (SSO’s) and combined sewer overflows (CSO’s) with the end goal of improving stream water quality. The agreement, now called Clean H2O40, is to meet target reduction metrics every five years through the final deadline of January 1, 2040. By 2040, SD1 will have eliminated SSO’s and will recapture at least 85 percent of the combined system overflow in a typical year. SD1 has made efforts to characterize and improve conditions within this region and these characteristics are considered in prioritizing watersheds, identifying specific sources for improvement, and identifying data gaps to be addressed in updated to the Watershed Plans. SD1 studies hydrology, water quality, aquatic habitat, and aquatic biology to understand the condition of the streams and to characterize pollutant sources and stressors.

One of the basic objectives of the Clean Water Act (CWA) is to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters. Due largely to the advancements in wastewater treatment and requirements regarding point source discharges, tremendous strides have been made toward the achievement of this, but much work (primarily in the area of storm water management) remains to be done. The current state of streams in Northern Kentucky watersheds covers a broad spectrum of conditions. The lesser disturbed, southern portion of Kenton County is traversed by higher quality streams, with recent biological assessments on portions of Cruise’s and Bowman’s Creek’s producing ratings, according to criteria established by the Kentucky Division of Water (KDOW) as “Fair”. Conversely, streams in the northern portions of the county have been subject to considerable impacts, and this is reflected in biological assessments of streams in the area.

In assessments from 2010, waterbodies in Kenton County are characterized as either “impaired” or “good.” Of the twenty-eight waterbodies in the watersheds of Kenton County, eight are considered “good” and the rest are “impaired.” Because streams are the endpoint of a watershed, their quality is a reflection of a culmination of activities within that watershed, and therefore, long term planning should take these types of assessments into consideration when developing strategies for future land use practices.

Headwater streams are integral to watershed health because they are the origins of the stream network, having unique characteristics that separate them from larger streams (Fritz et al. 2006). Disruption to these areas of the watershed can set off chain reactions that can migrate throughout the length of the stream. Best management practices are more successful and cheaper if they are applied to a site proactively rather than retroactively. For planning purposes within Kenton County, it is important to note that keeping a stream as high quality is less expensive than it is to restore it in the future. So, the level to which streams and waterways are impacted by land use activities should be carefully considered in the development process to ensure the least amount of damage possible is occurring to waterways – particularly at or near headwater areas.

SD1 regularly monitors the health of Kenton County’s watersheds and observes modeled bacteria sources and the causes of these bacteria. Data from this monitoring is analyzed to characterize stream conditions and identify potential pollutant sources. Kenton County is home to four main watersheds which are monitored by SD1. The vast majority of modeled bacteria sources for these watersheds come from runoff. This is particularly true in the two more northern watersheds – Pleasant Run Creek and Dry Creek. SD1 is working to develop more detailed watershed and water quality models to calculate water quality changes in response to new development, watershed controls and sanitary sewer controls. In the Banklick Creek watershed, modeled bacteria sources are largely attributed to SSO’s and in the Licking River watershed, septic systems contribute to modeled bacteria sources.

The Kentucky Environmental Protection Agency has also been focusing heavily on emerging contaminant research in recent years. Per- and Poly-Fluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS & PFOA) are the leading emerging contaminants since they are known as the “forever chemicals” and are very difficult to remove from the environment. Recent research and sampling has detected PFAS and PFOA in both source water and drinking water in Northern Kentucky.

The watersheds of the Northern Kentucky Region are located in the Outer Bluegrass Physiographic Region which is underlain primarily by Ordovician-age interbedded limestone and shale (Ray et. al., 1994). Although most of this watershed is underlain by bedrock with a moderate potential for karst development (Paylor and Currens, 2002), rocks in this region generally contain higher percentages of shale layers and do not develop extensive karst features (Ray et al., 1994).

The headwaters of this creek traverse the rolling hills of the Grant Lake Limestone / Fairview formation, which produces broad stream valleys. The middle portion of the creek, as well as some tributaries (Fowler Creek, Bullock Pen Creek) cut through the erodible shale found in the Kope formation. Downstream of Bullock Pen Creek, Banklick Creek traverses alluvium comprised of unconsolidated sediments. Groundwater yield varies depending on geological formation. Except near the headwaters, groundwater is generally unavailable on ridge tops and hillsides. In contrast, wells in the valley bottoms may yield 100-500 gallons per day. This water is hard and may contain salt and hydrogen sulfide. Water obtained from the alluvium may also be high in iron (Carey and Stickney, 2004, Carey and Stickney, 2005).

Northern Kentucky and Kenton County are characterized by rolling hills with more gentle slopes in the headwaters. In the downstream half of the watershed, the ground tends to slope steeply toward the creek. The adjoining hillsides and tributaries also have steep slopes; slopes in excess of 100 feet per mile are not uncommon for many of these tributaries. Slopes greater than 15% in Kenton County are more prevalent downstream along Banklick Creek and in the Cruise Creek watershed in southern Kenton County.

Current zoning and subdivision regulations set a threshold of 20% and greater for geotechnical investigations when development is proposed on steeper slopes. Plans must be submitted which show topography, any physical changes to the site necessary for construction, grading, compaction, erosion, sedimentation basics, and areas to be defoliated. A geotechnical investigation must be pursued to show that any structural or physical changes proposed will be completed in a manner minimizing hillside slippage and/or soil erosion.

The Kentucky Building Code (KBC) addresses the placement of buildings and structures on or adjacent to slopes steeper than 33.3 percent. The KBC specifies minimum setback and clearance of buildings and structures from the top and bottom of slopes. These setbacks and clearance distances are based on the height of the hill. Buildings or structures can however be placed within these minimum setbacks and clearance areas after investigation and recommendation from a registered design professional. Such an investigation includes consideration of material, height of slope, slope gradient, load intensity and erosion characteristics of the slope material.

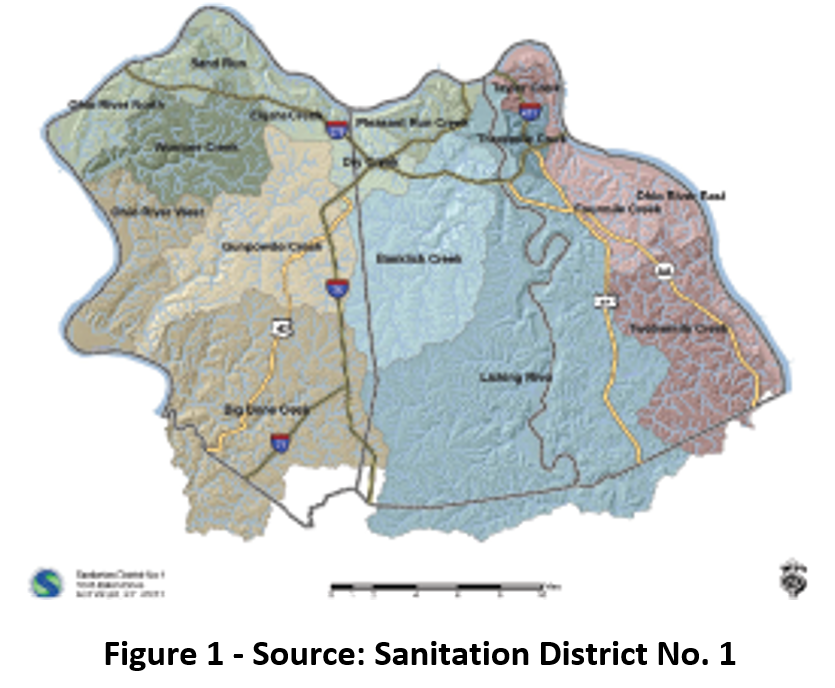

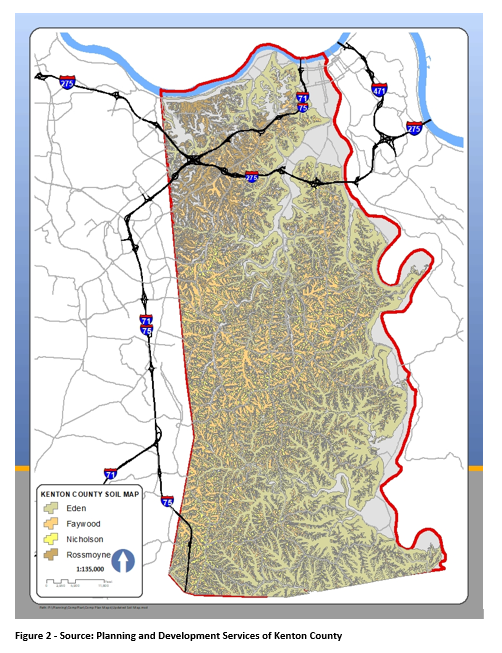

The nature of soils and topography in a watershed play an important role in both the amount of runoff generated and the amount of soil erosion that can occur. The top five soils in Kenton Count make up nearly 73% of the landscape as shown in Figure 2 These soils are of three different soil series and three different soil types. A soil series generally describes a soil’s consistency, permeability, geographic location/ lay, and slope on the landscape. The top five soils in Kenton County consist of soils from the Eden series, the Faywood series and the Nicholson series. A soil’s type indicates some of the general characteristics of a soil’s potential productivity. The top five soils in Kenton County consist of Silt Loam, Silty Clay Loam, and Silty Clay. See Figure 3 for more information.

The top five soil types in Kenton County and their respective percentage of land cover in the county are as follows:

- EdE2: Eden silty clay loam, 20 to 35 percent slopes, eroded – 30.23%

- FdD3: Faywood silty clay, 12 to 20 percent slopes, severely eroded – 16.373%

- NlB: Nicholson silt loam, 0 to 6 percent slopes – 9.29%

- NlC – Nicholson silt loam, 6 to 12 percent slopes – 8.35%

- FcD: Faywood silty clay loam, 12 to 20 percent slopes – 7.85%

Soil Series

- The Eden series of soils consists of moderately deep, well drained, slowly permeable soils. These soils are on hillsides and narrow ridge tops with slopes ranging from 2 to 70 percent but are predominantly 20 to 30 percent. Eden soils are well drained, runoff is medium to rapid, and permeability is slow. Most areas are used for pasture and hay, but some steeply sloping areas have reverted to forest or brushy pasture. Some broader ridge tops are used for tobacco, corn, and small grains.

- The Faywood series of soils consists of moderately deep, well drained soils which are found on ridge tops and side slopes of dissected uplands. Some areas have rock outcrops and some are karst. Slopes range from 2 to 60 percent. Faywood soils are well drained, runoff is medium or rapid, and permeability is moderately slow to slow. Most areas are used for growing hay and pastures. Some areas are used for growing corn, small grains, and tobacco. A few areas are idle or wooded.

- The Nicholson series of soils consists of very deep, moderately well drained soils. These soils are on nearly level to rolling upland ridge tops and shoulder slopes. Slopes range from 0 to 20 percent, but commonly are 12 percent or less. Nicholson soils are moderately well drained, negligible to medium runoff, and permeability is moderate above the fragipan and slow or very slow in the fragipan. Nearly all areas are used for growing corn, barley tobacco, small grains, truck and fruit crops, hay, pasture, and for urban-suburban development.

- The Rossmoyne series of soils consists of very deep moderately well drained soils that are moderately deep to a fragipan. Slopes range from 0 to 25 percent. These soils are formed in loess and the underlying till. Rossmoyne soils are good for general farming including corn, wheat, soybeans, grass, legumes, and tobacco. Some areas are used for pasture or woodland and others are left idle.

Soil Types

Silt Loam soils are generally known as the “average” soil types. They achieve a good balance between the ability to be very productive and the minimum attention necessary. Silty Clay Loam and Silty Clay soil types are difficult to work and manage; however, they usually have good supplies of nutrients and lime. The main drawbacks are the high-water holding capacity (which means they are late to get going in spring) and the effort required to work them. The right weather conditions are necessary to avoid hard work and damage to the soil structure. The use of heavy machinery (and especially rotavators) should be avoided at all costs, particularly when the soil is wet.

The Comprehensive Plan Update 2006 – 2026 had previously used the term Physically Restricted Development Area (PRDA) to alert developers and legislative bodies of areas that have moderate or steep slopes, sensitive geology, soils subject to occasional or frequent flooding, or a combination of these characteristics and which may require further site and geologic examination prior to construction and excavation activity. Following The Hills Project, detailed later in this report, a recommendation was made to change the name to Developmentally Sensitive Areas (DSA) in order to prevent potential perceived biases against development on said sites. DSA will also be used as an overlay with an underlying recommended land use. Figure 3 illustrates an analysis of subsurface sensitivity using three natural features including slope, soil, and geology.

The following sections describe key features of local watersheds and receiving streams, including hydrology, geology, topography, soils, and habitat. These features are important because they affect land uses, and shape the hydrological, chemical, biological, and characteristics of Kenton County watersheds.

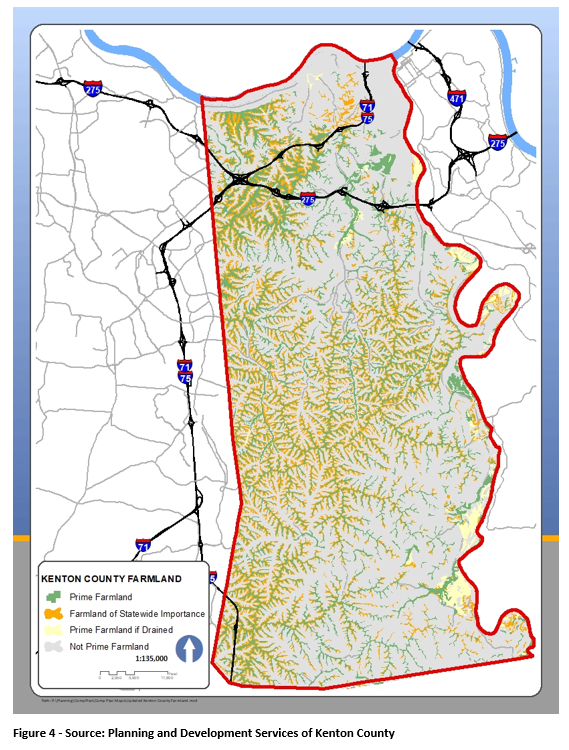

Kenton County consists of some soils which are considered Prime Farmland soils or Farmland of Statewide Importance as shown in Figure 4. Prime Farmland is land which consists of soil that has the best combination of physical and chemical characteristics for the production of crops. It has the soil quality, growing season, and moisture supply needed to produce sustained high yields of crops when treated and managed, including water management, according to current farming methods. Areas of Kenton County listed as Farmland of Statewide Importance indicates land other than Prime Farmland which has a good combination of physical and chemical characteristics for the production of crops.

The watersheds of Kenton County can generally be characterized by sinkholes, springs, entrenched rivers, and intermittent and perennial streams (Woods et al. 2002). Wetlands are not common in this ecoregion. Streams typically have relatively high levels of suspended sediment and nutrients. Glacial outwash, which tends to be highly erodible, exists in a few areas within this ecoregion.

Pre-settlement conditions in this ecoregion consisted of open woodlands with barren openings and vegetation was mostly oak-hickory, with some white oak, maple-oak-ash and American beech-sugar maple forests (Woods et al. 2002). Natural habitats have been altered from pre-settlement conditions by human development.

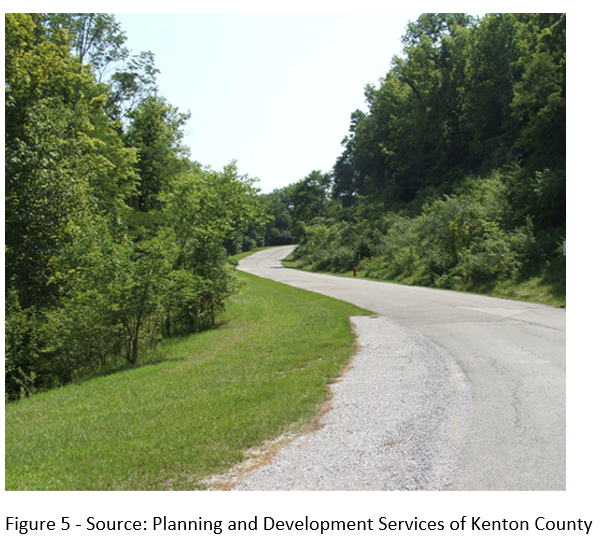

As Kenton County continues to develop, available flat land is reduced and much of the remaining land areas to be developed consist of steep, heavily wooded hillsides as depicted in Figure 5. Increased interest in urban living, the convenience of amenities, and magnificent views of the Ohio River and downtown Cincinnati are making development of previously untouched hillsides feasible. The hills and landscape of Northern Kentucky hold a variety of values and meaning for the people of this community. Land use has been undergoing change. These changes have community implications for quality of life in the short term as well as long term. Understanding the opportunities and constraints relative to health, safety, and welfare is essential.

As Kenton County continues to develop, available flat land is reduced and much of the remaining land areas to be developed consist of steep, heavily wooded hillsides as depicted in Figure 5. Increased interest in urban living, the convenience of amenities, and magnificent views of the Ohio River and downtown Cincinnati are making development of previously untouched hillsides feasible. The hills and landscape of Northern Kentucky hold a variety of values and meaning for the people of this community. Land use has been undergoing change. These changes have community implications for quality of life in the short term as well as long term. Understanding the opportunities and constraints relative to health, safety, and welfare is essential.

Discussion about the region’s hillsides began in the first comprehensive plan for Kenton County adopted in 1972. This plan identified a conservation category on the county’s recommended land use map which identified slopes which were 20 percent or greater. While the plan recommended restrictions for intensive urban development in these areas, a further study of Northern Kentucky’s hillsides was also recommended.

Subsequent comprehensive plans used the term Physically Restrictive Development Areas (PRDA) in place of the Conservation land use category later shifting to the Developmentally Sensitive Area (DSA) designation which is used as an overlay with an underlying recommended land use. The policy recommendation for DSA areas continued to be cautious in scope particularly when the type of geologic formation called Kope was present. In 1994, the Hillside Trust pursued a study titled A Hillside Protection Strategy for Greater Cincinnati that covered Hamilton County in Ohio and Kenton County in Northern Kentucky. The study identified critical hillsides and provided several recommendations, including guidelines for development on hillsides. Other geological components, such as soil and geology, were also assessed in determining the severity of potential impacts from further development on DSA designated areas of the county.

In 2008, the Department of Landscape Architecture from the University of Kentucky assisted PDS to begin public discussions on hillsides. Three public meetings were held over a four-month period in early 2008. Stakeholder participation and survey activities were used to gather insight and ideas. Collectively, over 200 residents attended these meetings to provide input. While this was a student project, it brought to light the level of public interest with regards to hillsides in Kenton County. The students opened the public discussion with varying scenarios of development patterns and assessed the costs and benefits for these approaches.

PDS undertook the second phase of The Hills project in late 2009 with the goal of continuing discussion began by the UK students and building consensus on the future of hillsides in Kenton County. The Hills project was designed to solicit public opinion on how Kenton County residents feel about its largely undeveloped hillsides and to build public consensus on how this community should respond to growing pressure to develop on its hillsides. This outreach effort included online surveys, forum discussions with panels of experts, close work with a technical task force, as well as communication and discussion with many different stakeholders throughout the community.

In October 2009 the first public opinion survey was posted online for two weeks to obtain public input on the future of hillsides. Four hundred Kenton County residents participated in the survey. 88% of the respondents indicated that hillsides were important to them. 35% of those said hillsides were important due to environmental benefits while 27% said they were important due to potential for development. 54% of the respondents indicated that single family development was appropriate on hillsides but were split on the appropriateness of multi-family on hillsides. Over 65% felt that non-residential uses were inappropriate on hillsides. This survey was used an as tool to gauge the community’s initial thoughts as it related to hillsides.

Over 120 people attended the first public forum that was held in December 2009. A 16-person panel of design, development, and public policy professionals facilitated the public forum, and a Northern Kentucky University communications professor moderated. The setting allowed the public to ask questions of the panel and vice versa. Forum participants answered questions through an audience response system where each person used a keypad to respond. Their responses were tabulated immediately and projected on a screen.

Several general themes came from the first public forum and include the following:

1. The need to preserve hillsides for their beauty and to maintain the character of Northern Kentucky is important.

2. The rights of property owners who own land on these hillsides are important.

3. The downhill impacts of storm water runoff from hillside developments should be considered.

4. Today’s 20 percent slope threshold (for a more intense review process) should be assessed to determine its effectiveness.

5. This is an important issue and those in attendance want to continue to participate in it.

A second public forum was held in May 2010 to continue the discussion on hillsides in Kenton County. A 16-person panel of design, development, and public policy professionals took part in the forum. Over 30 people were in attendance at this meeting. The panel and audience agreed that there is a need for both conservation and development of hillsides, and that a balance between the two is necessary. As a result of the second public forum it was concluded that there is a need to initiate a meeting with local technical professionals who work with hillside issues regularly—to get their expertise on engineering and technical design aspects and how they relate to developing hillsides.

The third public forum was held in September to continue the discussion on the future of hillsides in Kenton County. A 16-person panel of design, development, and public policy professionals took part in the forum. Over 50 people were in attendance at this meeting. This forum was mainly focused on the topic of hillside conservation. Four additional topics of interest surfaced at the meeting:

1. Non-monetary ways to conserve hillsides such as a donation of property by interested donors to a conservation group;

2. The importance of focusing conservation efforts on land that has ecological value, based on the Forest Quality Assessment that was done for Kenton County;

3. The importance of considering individuals’ economic status when crafting recommendations;

4. The importance of analyzing hill slides that have already occurred in Kenton County and any associated repairs, as well as understanding if the slides occurred naturally or because of poor development practices.

A significant piece of The Hills project outreach included a scientific opinion survey conducted by Levin & Associates to gauge the level of public interest in hillsides. An overview of the type of data that would provide insight into the level of public interest was used as a foundation for the questions pursued. An independent third party administered the phone survey. For Kenton County, a sample size of 300 complete responses was needed to create a scientific survey with a margin of error +/- 6.5%. The following were main conclusions drawn from the survey:

1. Most respondents prefer a mix of hillside development and preservation.

2. More than half want the community to place a high or very high priority on preservation.

3. One third of the respondents care deeply about Kenton County hillsides and favor full preservation.

4. 80 percent of the respondents agree or strongly agree that undeveloped hillsides add to the visual appeal of Kenton County.

5. 65 percent of respondents agree or strongly agree that preserving hillsides is an appropriate use of our community’s resources.

6. Just 10 percent of the respondents said they don’t care about hillsides.

7. More than half of the respondents indicated that they would be interested or extremely interested in any decisions made regarding hillsides in Kenton County.

All concerns and ideas expressed during this year long discussion were grouped into one of the following three categories along with findings and conclusions:

1. Engineering – Geotechnical investigations, safety, and enforcement:

Findings:

• Within current regulations, geotechnical investigations are required when land disturbance is proposed on slopes equal to or greater than 20 percent on that portion of land. This threshold of 20 percent is consistent with the current policy guidance provided in the comprehensive plan.

• Kope formation, a geology that is susceptible to slippage, is often present on slopes greater than 20 percent.

• When a geotechnical investigation is performed and the recommendations from the report are followed, the project has a high probability of being safe and successful.

• The current, single “trigger” of disturbing existing slopes equal to or greater than 20 percent that prompts the geotechnical professional to become involved is a one-dimensional, limited threshold.

Conclusions:

• The current threshold of 20 percent for when geotechnical investigations are required and do not need to be increased or decreased.

• When geotechnical investigations are performed the recommendations contained therein should be required to be followed. A certification letter indicating compliance with the recommendations should be required from the geotechnical engineer of record. This recommendation is included in the new zoning ordinances which several jurisdictions in the community have adopted or are in the process of adopting.

• While the current single threshold of proposed slopes equal to or greater than 20 percent is sufficient for the purposes of requiring further geotechnical investigation, additional triggers should be considered. These should take into consideration other factors such as those that influence hillside stability and assessment of potential impact beyond a particular site.

- 2. Land Development – Balance of preservation and development

- Findings:

• Public opinion surveys and input received at the public forums indicate that there is a desire in the community to address the need for true preservation of hillsides.

• Concerns also exist regarding the rights of property owners to develop their land.

• Public opinion also indicates that the general consensus is to see a balance of preservation and development.

Conclusions:

• Alternative policy recommendations should be made that provides guidance on how true preservation may be pursued without affecting the rights of property owners.

• While there was a general consensus that hillsides add to the character of northern Kentucky, aesthetics is one factor that is hard to define and quantify.

• There is a need to identify hillsides worthy of preservation using elements such as Geologic (Kope formation, Landslide prone areas), Ecological (Wildlife corridor and Endangered species) and Environmental (Tree canopy, slopes) features.

- 3. Site Design – Density, flexibility in design and aesthetics

Findings:

• Most ordinances do not differentiate site design controls based on terrain. Requirements for setbacks, infrastructure and height are the same on hilly terrain as on flat land.

• The Physically Restrictive Development Area (PRDA) (now referred to as Developmentally Sensitive Areas, or DSA) in the comprehensive plan, while providing caution for development, does not provide any guidance on density of development on hillsides.

• No clear public opinion on the location of development on a hillside (i.e.) top, bottom or middle emerged. But there was a clear indication of support for development that was clustered with the disturbance of vegetation minimized.

Conclusions:

• There is a need to identify hillsides worthy of preservation using elements such as Geologic (Kope formation and landslide prone areas), Ecological (Wildlife corridor and endangered species) and Environmental (Tree canopy and slopes) features.

• The areas identified as worthy of preservation should be the areas targeted for providing an alternative form of development that is sensitive to the natural elements of hillsides.

• Since site design issues are unique to each site, a review process that is more design based and flexible in requirements should be explored.

Impervious surfaces, such as paved roads and parking lots, and roof tops are a primary cause of water contamination and urban/suburban flooding. Flooding is directly related to the physical layout of the land and surface treatments. Impervious surfaces prevent water from entering the ground where it can be cleansed and slowly released into the surface drainage system or recharge aquifers. Water running over impervious surfaces picks up contaminants and flushes concentrated volumes of pollutants directly into streams and rivers. Vegetation on the landscape can act as a buffer to decrease the speed and volume of water running over the surface of a site by allowing storm water to filter through rather than run across. In addition, it also increases the speed at which water flows into the storm water drainage system or stream network thus overwhelming the carrying capacity of both natural streams and storm water facilities causing flooding. In a natural setting, 50% of water is allowed to infiltrate into the soil and 10% is runoff. After development, infiltration can decrease to 15% and runoff can increase to 55% which can lead to stream degradation.

Across Kenton County, the overall estimate of impervious surface coverage as of2024is about 9.6% of the total land area, however, each of the four main watersheds monitored by SD1 within Kenton County are very different. These calculations help to create a better understanding of why runoff is often a top contributor to pollutants found within our waterways particularly when paired with a more in-depth analysis of each of the four watersheds monitored within Kenton County. Natural features, which work to filter pollutants and lessen volume of water movements, are less able to adequately facilitate water movement; and therefore, are less able to prevent flooding, landslides, or contamination within the waterways. SD1 has compiled Fact Sheets describing each of these watersheds, their characteristics, and identification of impaired waterways. An excerpt from these Fact Sheets can be found below. Increasing amounts of impervious surface paired with decreasing amounts of tree canopy cover leads to larger amounts of runoff into our waterways.

Banklick Creek

The Banklick watershed, a tributary of the Licking River, is one of the largest watersheds within Kenton County (nearly a third of the county’s land area), is highly developed in the downstream portion and flooding is a recurring problem in this area. Farther upstream, the watershed is less developed. This portion of the watershed is rapidly developing and Banklick Creek is predicted to have the largest amount of new development of all the study area watersheds. The Banklick Creek Watershed Council is actively working to improve stream conditions in this watershed. With a drainage area of 58.2 square miles, the land cover for this watershed is currently characterized as 11% impervious surface and is predicted to be 17% impervious surface by the year 2030. The entire length of this creek is impaired due to fecal coliform bacteria, nutrients and organic enrichment. The lower 8.2 miles are also impaired due to sedimentation. Doe Run Lake is impaired due to low dissolved oxygen, bacteria and other microbes, nitrogen and/or phosphorus, and sediment.

Dry Creek

The small Dry Creek watershed is the second most highly developed watershed. A portion of this watershed lies within Florence, outside SD1’s sanitary sewer and storm water service area; however, the majority of this watershed lies within Kenton County including cities such as Erlanger, Crestview Hills, Crescent Springs, and Villa Hills. SD1’s Dry Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant lies within the watershed. This facility receives and treats wastewater from many other watersheds, and discharges treated effluent directly to the Ohio River. With a drainage area of 12.4 square miles, the land is covered by 24% impervious surface and is expected to be covered by 28% impervious surface by the year 2030. Currently, 6.8 miles of Dry Creek are identified as impaired due to nutrients and organic enrichments.

Licking River

The entire Licking River watershed is approximately 3,600 square miles and extends 300 river miles to Magoffin County, KY. For this study, the Licking River watershed is defined as the area between the mouth and river mile 35.6, (beyond Kenton County’s southern boundary) excluding two tributaries, Banklick Creek and Three Mile Creek. This watershed is highly developed between Wilder and its confluence with the Ohio River. Farther upstream, land use transitions to more rural uses dominated by forest and agriculture uses. There are two public drinking water intakes from the Licking River that are located in this watershed. With a drainage area of 170 square miles, the land cover is only 3% impervious surface and is expected to increase to 4% impervious surface by the year 2030. The Licking River has three segments identified as impaired due to fecal coliform. This segment totals 19.5 miles within SD1’s monitoring area.

Pleasant Run Creek

Pleasant Run Creek drains a small and very highly developed watershed. Much of the undeveloped land that remains is located within Devou Park, near the mouth of this creek. The drainage area of 6.5 square miles is covered by 18% impervious surface and is expected to be covered by 19% impervious surface by the year 2030. There are no state impaired waters within this watershed.

Banklick Watershed Council

The Banklick Watershed Council (BWC) is dedicated to the improvement of Banklick Creek and its watersheds. The BWC has established four main goals through the Banklick Watershed Action Plan. These goals are to clean the water, reduce flooding, restore the banks, and honor the heritage of the watershed. These goals are accomplished through watershed council programs including land conservation, stormwater management, septic repair, and pasture management. This report was prepared initially in 2005 and later updated in 2010 specifically to plan for federal EPA grant projects. Funds are only available to watershed councils that have taken the steps of creating a detailed action plan. This plan has been developed to guide the Banklick Watershed Council and all its partners in watershed improvement efforts, but it is further hoped that it will stimulate watershed residents, businesses, and others to join in those efforts.

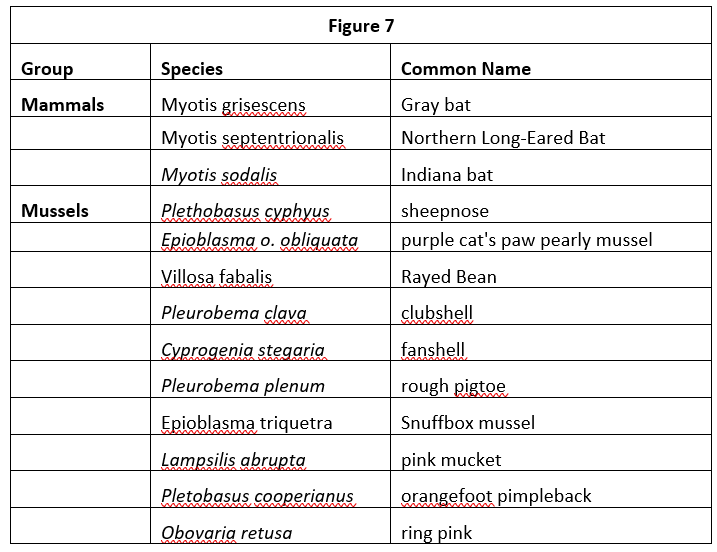

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service maintains a database of collection records of protected species within Kenton County. This list, containing federally listed species which have the potential to occur within Kenton County can be found in Figure 7.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service maintains a database of collection records of protected species within Kenton County. This list, containing federally listed species which have the potential to occur within Kenton County can be found in Figure 7.

Mammals

Kenton County is located within a habitat designated as “potential habitat” for three endangered bat species and U.S. Fish and Wildlife believes that: (1) forested areas in Kenton County may potentially provide suitable summer roosting and foraging habitat; and (2) caves, rock shelters, and abandoned underground mines in Kenton County may potentially provide suitable wintering habitat for these bat species. These bats utilize a wide array of forested habitats, including riparian forests, bottom lands, and uplands for both summer foraging and roosting habitat. Prior to hibernation, bats utilize the forest habitat around the hibernacula (i.e. cave) to feed and roost until temperatures drop to a point that forces them into hibernations. This “swarming” period is dependent upon weather conditions and lasts from mid to late fall. This is a critical time for bats, since they are acquiring additional fat reserves and mating prior to hibernations. Research has shown that bats exhibiting this “swarming” behavior will range up to five miles from chosen hibernacula during this time. For hibernation, the bats prefer limestone caves, sandstone rock shelters, and abandoned underground mines with stable temperatures Native Kentucky bats have suffered as a result of human disturbance during hibernation, loss of natural habitat, and flooding caused by manmade impoundments. Pollution and siltation of streams and increased pesticide use can reduce their food sources as well. The Indiana bat has been critically affected by the fungal disease, White-nose syndrome resulting in high levels of mortality.

Federally Listed Mussels

Freshwater mussels are one of the most imperiled groups of animals in North America. Reservoir construction, siltation, channelization, and water pollution are all factors that have contributed to the decline of our native mussel populations. The runoff from urban areas has degraded the quality of water and the substrate of many streams. As filter feeders, mussels are sensitive to contaminants and function as indicators of problems with water quality. Several species of federally listed mussels are known to exist in Kenton County, particularly in the Ohio River and the Licking River. The potential of development to impact federally listed mussel species, either directly or indirectly as a result of siltation/sedimentation and contamination, should be addressed when evaluating the proposed project.

Further Information

Additional information about threatened and endangered species within Kenton County can be found in the Kentucky State Nature Preserve Commission’s Report of Endangered, Threatened, and Special Concern Plants, Animals, and Natural Communities. The report was last updated in 2019.

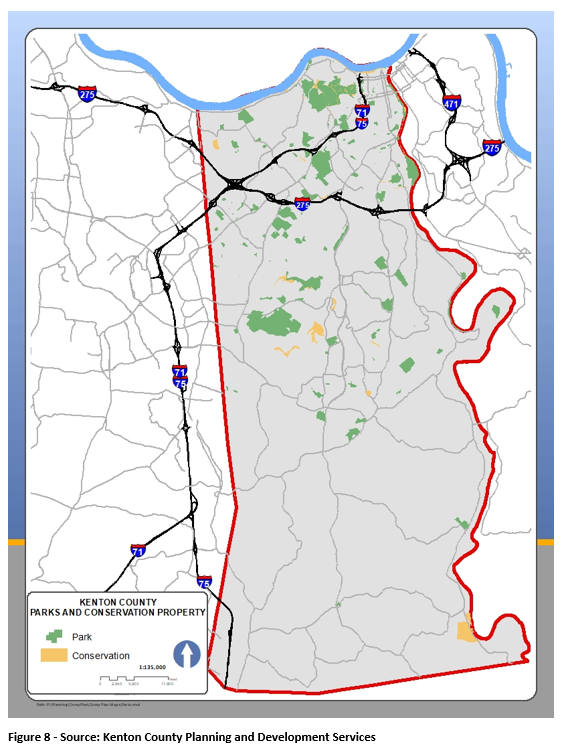

Kenton County has more than 84 parks open to the public. These parks cover more than 2,400 acres of the county and provide both passive and active recreational spaces for Kenton County residents. The vast majority of these parks are managed and maintained by individual cities within the county; however, Kenton County maintains eight parks throughout the county, adding up to over 700 acres of open and recreational space. This includes a new 225-acre Kenton County Park in Independence that was formerly part of Fox Run Golf Course before being converted to a park in August of 2020. Some cities within the county do not have any parks of their own and their residents rely on neighboring cities or the county for outdoor recreational opportunities. See Figure 8.

Kenton County has more than 84 parks open to the public. These parks cover more than 2,400 acres of the county and provide both passive and active recreational spaces for Kenton County residents. The vast majority of these parks are managed and maintained by individual cities within the county; however, Kenton County maintains eight parks throughout the county, adding up to over 700 acres of open and recreational space. This includes a new 225-acre Kenton County Park in Independence that was formerly part of Fox Run Golf Course before being converted to a park in August of 2020. Some cities within the county do not have any parks of their own and their residents rely on neighboring cities or the county for outdoor recreational opportunities. See Figure 8.

The largest single park within Kenton County is Devou Park at 704 acres with a multitude of passive and active recreational opportunities, most recently adding a disc golf course to the list of amenities. This park, due to its size, location, and amenities does provide a regional draw for those seeking outdoor recreational opportunities. Devou Park is just one of the 24 parks operated and maintained by the City of Covington.

Open space refers to unbuilt land areas which includes forests, publicly owned parks, and nature preserves. These spaces provide the aesthetic beauty that defines Northern Kentucky and serves important environmental functions such as floodplains, wildlife habitats and buffer zones from more intense development.

There are two local organizations, the Kenton Conservancy and the Kenton County Conservation District whose mission includes preserving open space in perpetuity for all generations to enjoy.

The Kenton Conservancy

In addition to public parks maintained by municipalities, the Kenton Conservancy owns nine properties. The Kenton Conservancy is a non-profit volunteer organization committed to preserving lands of natural, cultural, recreational, and historical significance within Kenton County. This organization facilitates significant land conservation through voluntary contributions, conservation easements, donations of property and purchases in support of a high quality of life and stable economic future. This organization is an economic resource for preservation of land to benefit communities and natural systems and works to form meaningful partnerships with all stakeholders in the community: private landowners, farmers, developers, local governments, businesses and concerned citizens. To date, the Conservancy has acquired properties totaling over 250 acres and the Kenton Conservancy continues to seek opportunities to grow the amount of preservation land within the county.

The Kenton County Conservation District

The Kenton County Conservation District is a special purpose government entity responsible for carrying out a comprehensive program to protect soil, water, and other natural resources. It works closely with the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service and the KY Cabinet for Environmental and Public Protection. The county conservation district is a part of the Kentucky Division of Conservation under the Kentucky Department for Natural Resources. The mission of the district is to ensure that sound land use activities, the prevention of soil erosion, water quality protection, and other environmental quality issues are given due consideration and priority in the management of Kenton County’s natural resources. This will maintain and improve the quality of life in Kenton County. The Kenton Conservation District maintains 222 acres of designated open space in the southern portion of Kenton County.

The air quality of our region is monitored across local jurisdictional boundaries by the Ohio-Kentucky-Indiana Regional Council of Governments (OKI). OKI is the federally designated regional transportation planning entity for the eight county, tri-state region. Transportation plays an important role in the region’s quality of life with significant social, environmental, and economic consequences.

In the 2050 OKI Regional Transportation Plan, the community renews their regional commitment to clean air through recommended behavior-based strategies. These strategies are aimed to reduce vehicle miles traveled by creating alternatives to roadway expansions such as shifting trips out of peak travel periods (rush hour) and eliminating some trips all together by increasing telecommuting and flexible work schedules, expanding rideshare programs, parking management, growth management planning and new opportunities for bicycle and pedestrian travel. OKI’s Regional Transportation Plan also looks to improve transit as a component of air quality and to continue to provide valuable information to the community regarding awareness of air quality issues.

Due to the interconnected nature of transportation and quality of life, OKI assesses and monitors air quality for the Northern Kentucky/Kenton County region based on the Clean Air Act Amendments (CAAA) of 1990. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is most recently reporting that the Kenton County region has reached attainment levels in five of the six regulated air pollutants. These six air pollutants include sulfur dioxide, lead, carbon monoxide, particulate matter, and ozone. OKI reports that the region is now at attainment levels for PM 2.5 fine particulates as of 2012. As of 2015, the region remains at non-attainment levels for Ozone, meaning that it is not meeting the national ambient air quality standard. Emissions of greenhouse gases, although not EPA-regulated pollutants based on the CAAA, are also being considered in OKI’s Transportation Plan because of their relationship to climate change. OKI has policies in place to address these issues and while much progress has been made in reducing mobile source emissions, travel growth over the next several years may cause concern for the region’s ability to maintain federally mandated clean air standards.

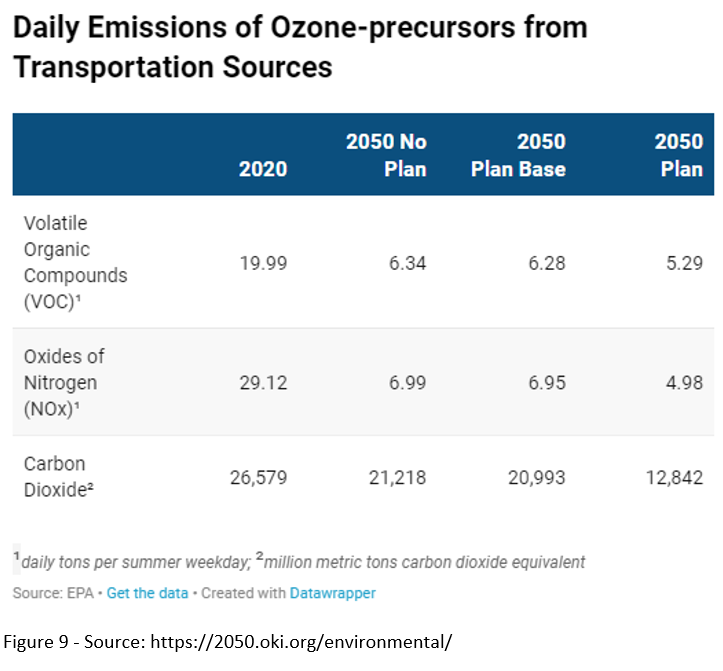

Air Quality Impact

At the regional level, the effect of vehicle emissions on air quality is a major consideration in transportation planning. Individual vehicle trips may seem insignificant, but their cumulative effect is a major determinant of an area’s air quality. The air quality impacts of the 2050 Plan have been forecasted using OKI’s Travel Demand Model and EPA’s Emissions Model. As shown in Figure 9below, the 2050 Plan will result in fewer vehicle emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOC), oxides of nitrogen (NOx), and greenhouse gases (expressed as carbon dioxide equivalent).

1. Sanitary sewer overflow: A sanitary sewer overflow (SSO) can occur when sewer system capacity is exceeded due to wet weather, when normal dry weather flow is blocked for any of several reasons, or when mechanical failures prevent the system from proper operation.

2. Combined sewer overflow: During rain events or snowmelt, combined sewer systems are designed to overflow when the sewer system capacity is exceeded, resulting in a combined sewer overflow (CSO) that discharges directly to surface waters such as rivers, streams, estuaries, and coastal waters.

3. Source: Sanitation District 1 https://www.sd1.org/

4. Sanitation District No. 1. Updated Watershed Plan for Northern Kentucky. https://www.sd1.org/DocumentCenter/View/1467/Updated-Watershed-Plan—May-2021-Edited-Version. May 13, 2021.

5. Physiographic regions are based on differences in geology, topography and hydrologic regime. The State of Kentucky is divided into five physiographic regions

6. In areas with karst, an almost immediate connection between groundwater and surface water can exist, short-circuiting any attenuation of pollutant loads that might otherwise occur.

7. https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/OSD_Docs/E/EDEN.html

8. https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/OSD_Docs/F/FAYWOOD.html

9. https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/OSD_Docs/N/NICHOLSON.html

10. Fragipan – A loamy, brittle subsurface horizon low in porosity and content of organic matter and low or moderate in clay but high in silt or very fine sand. A fragipan appears cemented and restricts roots. When dry, it is hard or very hard and has a higher bulk density than the horizon or horizons above. When moist, it tends to rupture suddenly under pressure rather than to deform slowly. Source: http://websoilsurvey.sc.egov.usda.gov/app/WebSoilSurvey.aspx

11. Characteristics of Different Soil Types – https://www.rhs.org.uk/soil-composts-mulches/soil-types

12. Prime Farmland does not include publicly owned lands for which there is an adopted policy preventing agricultural uses.

13. Farmland of Statewide Importance does not include publicly owned lands for which there is an adopted policy preventing agricultural use.

14. Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and quantity of environmental resources (Woods et al., 2002).

15. Kope soil formation: Kope is a clay-shale rich, flat-lying geologic formation that can reach over 200 feet thick in the Northern Kentucky region. In undisturbed conditions, the clay and shale help to maintain Kope stability; however, when development cuts increase the exposure of the particles to air and water, they begin to break down mineral size particles into clay. The materials found at the surface layer of a Kope formation have a heightened propensity to slide under these circumstances. Because the bedrock underlying Kope formations is significantly more stable, structures built on these conditions will often bypass through the Kope and anchor into the bedrock beneath (Agnello, 2005).

16. The Hillside Trust’s mission is accomplished through research and education, land conservation, and advocacy of responsible land use serving: Cincinnati and Hamilton County, along with the surrounding counties of Clermont, Campbell, Kenton, and Boone. Beautiful and fragile, the Greater Cincinnati area is prone to costly landslides. Concern over this problem is increasing as the scarcity of land gives rise to pressures to build. The landslide-prone nature of our hillsides is not the only concern. The forested hillsides form ribbons of green open space, and are a valuable element of environmental quality, providing wildlife habitat and migration corridors. The hillsides form an integral part of the natural fabric of Greater Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky.

17. How’s My Waterway? United States Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed October 31, 2023 from https://mywaterway.epa.gov/

18. Water Health Portal. Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet. Accessed October 31, 2023 from https://water-health-portal-kygis.hub.arcgis.com/

19. Based on the Kentucky Division of Water standards for water quality. water.ky.gov

20. The Banklick Watershed Council. Accessed January 26, 2023 from banklick.org

21. Northern Kentucky Urban and Community Forestry Council. Accessed January 26, 2023 from https://nkyurbanforestry.wildapricot.org/

22. Davey Resource Group, Forest Quality Assessment Summary Report, Kenton County, Kentucky, October, 2004. Crown Class Sizes: Small = Less than 12” Diameter Breast Height (dbh), Medium = 12” to 18” dbh, Large = Greater than 18”. Forested tracts with a mix of crown sizes were classified using the predominant crown class. Adjacent tracts of canopy cover less than five acres of varying crown sizes were grouped and classified using the predominate crown class.

23. The Northern Kentucky Urban and Community Forestry Council. www.nkyurbanforestry.org

24. Vision 2015 is an intermediary organization championing a shared public plan that represents the region’s priorities. The plan contains specific action steps to achieve the region’s goals and measure the impact of those goals. Vision 2015 also has a broader role, bringing leaders and creative thinkers to the table in order to promote systematic, sustainable change.

25. Source: www.kentoncounty.org

26. “Listed species believed to or known to occur in Kenton, Kentucky.” U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Accessed January 26, 2023 from https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/report/species-listings-by-current-range-county?fips=21117

27. “Bats of Kentucky”. Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources. 2023. https://fw.ky.gov/Wildlife/Pages/Bats-of-Kentucky.aspx

28. “Freshwater Mussels and Aquatic Snails.” Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources. 2023. https://fw.ky.gov/Wildlife/Pages/Freshwater-Mussels-and-Aquatic-Snails.aspx

29. Covington Urban Forestry. Accessed on December 6, 2023 from https://www.covingtonky.gov/government/departments/public-works/urban-forestry

30. Endangered, Threatened, and Special Concern Plants, Animals, and Natural Communities of Kentucky. Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet – The Office of Kentucky Nature Preserves. Accessed October 31, 2023 from https://eec.ky.gov/Nature-Preserves/biodiversity/Documents/Rare_species_of_Kentucky.pdf

31. Particulate matter (PM) includes both solid particles and liquid droplets found in air. Many manmade and natural sources emit PM directly or emit other pollutants that react in the atmosphere to form PM. These solid and liquid particles come in a wide range of sizes. Particles less than 2.5 micrometers in diameter (PM2.5) are referred to as “fine” particles and are believed to pose the largest health risks. Because of their small size (less than one-seventh the average width of a human hair), fine particles can lodge deeply into the lungs. Health studies have shown a significant association between exposure to fine particles and premature mortality. Sources of fine particles include all types of combustion activities (motor vehicles, power plants, wood burning, etc.) and certain industrial processes. Source: United States Environmental Protection Agency – www.epa.gov

32. Ozone – Tropospheric, or ground level ozone, is not emitted directly into the air, but is created by chemical reactions between oxides of nitrogen (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOC). Ozone is likely to reach unhealthy levels on hot sunny days in urban environments. Ozone can also be transported long distances by wind. For this reason, even rural areas can experience high ozone levels. Ground level ozone- what we breathe- can harm our health. Even relatively low levels of ozone can cause health effects. People with lung disease, children, older adults, and people who are active outdoors may be particularly sensitive to ozone. Source: United States Environmental Protection Agency – www.epa.gov

33. Source: Ohio Kentucky Indiana Regional Council of Governments – https://www.oki.org/