About

Goals & Objectives

Elements

Research & Public Engagement

Mobility Report

Mobility refers to how people and goods move from point to point through different transportation options such as cars and trucks, public transportation, biking, walking, and air. Kenton County is home to nearly 169,000 residents that move in, around, and through the county on a daily basis utilizing all of the aforementioned modes. While modal choices are available, residents’ travels are primarily accomplished through a variety of roadways ranging from rural local streets which wind through the hills and valleys in the southern end of the county, to wide multi-lane major urban arterials, which traverse the county’s urban, suburban and first ring sub areas. Other mobility choices such as public transit, bicycling, and walking also exist in the county but are utilized by the public to a much lesser extent. Information in subsequent portions of this chapter will provide details about each transportation choice, their actual usage as reported by the US Census Bureau, and the network as it exists in Kenton County today.

This report also examines the role the county plays in the national transportation infrastructure by reviewing assets such as Interstate 71/75, the Brent Spence Bridge, the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport, railroads, and river freight. The county’s transportation system was last comprehensively studied in the 2014 Kenton County Transportation Plan.

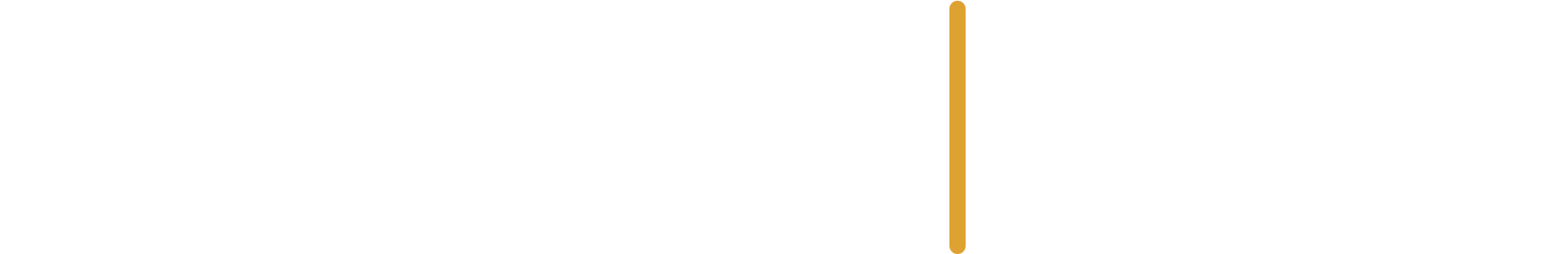

In 2022 the US Census Bureau estimated there are 90,475 workers in Kenton County age 16 or older, indicating they could meet the legal age requirement to drive a vehicle. Of this population, approximately 69.8 percent were identified as drivers who commuted to work in a single occupancy vehicle, 9.8 percent commuted to and from work in a car/vanpool mode, 0.8 percent utilized public transportation, 1.4 percent walked, and 1.2 percent used another means such as bicycle or taxicab to travel to work. The remaining 17 percent of workers were estimated as working from home. Compared to the rest of the nation, Kenton Countians travel more in single occupancy vehicles and utilize all other modes to a lesser extent as exhibited in Figure 1.

A further analysis of Figure 1 shows that while the overall number of workers age 16 and older in Kenton County has increased by 20 percent, there was a large reduction in the percentage of single-occupancy vehicle commuters in Kenton County. This is offset slightly by an increase in the number of workers who walked or relied on other modes of transportation. Kenton County experienced a 614 percent increase in the number of workers working from home. The Census data does not attribute this increase to a specific factor, but experience suggests that this change was largely brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The fact that Kenton County residents choose single occupancy vehicles nearly 70% of the time can be attributed to several different factors. Lower point- to-point travel times, convenience, and ease of use are often reported as reasons why people choose personal vehicles over other options. These, coupled with either service or facility limitations in the networks also help account for the over eight percent difference between local and national figures. These factors will be described in greater detail in subsequent sections. However, it should be emphasized that more single occupant vehicles operating on the network naturally results in greater congestion, higher delay, increased fuel consumption, and more wear-and-tear on roadway infrastructure.

Adjoining land uses play a critical role in how transportation networks function. More intensely utilized land in urban and suburban areas provides more people per net acre and, therefore, more users of the network. Additionally, the historical development of land plays a role in the effectiveness of mobility. For instance, residential uses in an urban area would likely be located on a grid network that gave users many route options in the form of intersecting streets. Suburban areas, however, more typically utilize a cul-de-sac form of development that sends high numbers of users out to arterial streets via minimal access points. While this form of development might be good for keeping through traffic away from residents, it can negatively impact traffic flow, especially if part of the network becomes blocked.

Kenton County has multiple forms of development across four unique sub areas (urban, first ring suburban, suburban, and rural). Historically, growth in the county started in the urban area and radiated outward along major arterials. In more rural areas, development traditionally grew up around major crossroads. Few limitations were placed on adjoining land uses and growth was allowed to occur with numerous curb cuts along major roadways. As a result, roads like Dixie Highway now experience increased congestion and higher crash concentrations from intense uses along the route.

As demand requires the addition of new roadways and street realignment, analysis of the impact of adjoining land uses should be considered. Care should be taken to increase safety along these and existing roadways by implementing carefully planned corridors that balance the public’s health, safety, and welfare and provide ample access to private property owners. The 2014 Kenton County Transportation Plan Update places an increased emphasis on the interrelatedness of land use and transportation.

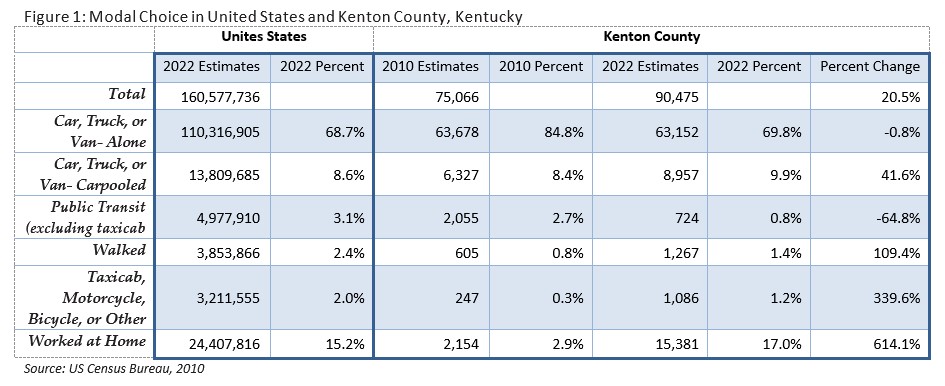

Analysis of the existing transportation network indicates that roadways are the most robust transportation system within the county. Within the county’s borders, there are approximately 1,000 miles of roadway. Over two-thirds of the network (694 miles) is comprised of local streets that primarily service residential land uses. The remaining third is distributed among interstates, arterials, and collectors. A map of all the functionally classified roadways is provided in Figure 2.

Functional classification of roadways is important because the order helps understand a roadway type and types of land uses that might adjoin the thoroughfare. For instance, an Urban Principal Arterial would likely be a four or five lane roadway located in an urban or suburban setting with multiple access points and differing land uses such as residential, commercial, or office along the route. A Rural Local roadway; however, would be a more winding one or two lane road with predominantly residential or agricultural uses adjoining the street and lower densities. Each roadway type is important to the overall net- work and helps identify where higher vehicular demands exists on the network. The classification scale also helps identify where new development might be most appropriate with supporting transportation infrastructure already in place.

In August 2018 the Kenton County Planning Commission adopted Kenton Connects as a part of Direction2030. Kenton Connects is a countywide project, which examines and makes recommendations for bicycle and pedestrian modes of transportation. Kenton County is home to nearly 169,000 residents that utilize all modes of transportation including cars and trucks, public transportation, bicycles, and by foot. While bicycling and walking are used less frequently than other modes of transportation, they are nonetheless important to Kenton County. Refer to the Kenton Connects research report for more detailed information and recommendations regarding bicycle and pedestrian facilities.

Public transportation refers to a system that charges fares to carry passengers on fixed routes within vehicles available to the public such as buses, subways, and/or trains. This mobility choice helps to reduce single occupancy vehicles within the transportation system, alleviating congestion, reducing delays, and lessening the overall emissions by carrying several passengers in one vehicle.

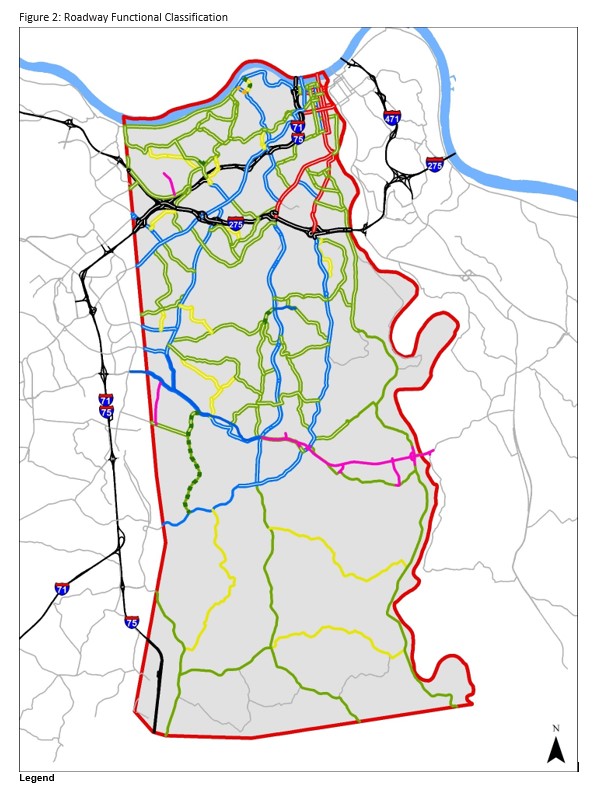

In Kenton County, public transportation is predominantly conducted within a hub and spoke bus system. In other words, routes pulse between the suburban sub area and the hub in the urban sub area of downtown Covington, Newport and Cincinnati (by extension). With the addition of suburban employment centers over the last 15 years, the traditional hub and spoke bus model has become bi-directional, bringing people from the suburbs to work downtown and bringing urban residents to the growing job centers, primarily in Boone County, near CVG.

Kenton County’s public transportation is provided by the Transit Authority of Northern Kentucky (TANK). TANK is part of the regional transit system that serves Northern Kentucky (also comprised of Metro in Southwestern Ohio). TANK operates seven local routes including the Southbank Shuttle, two express routes, and several Park & Ride locations in Kenton County. The system also operates two transit hubs inside Kenton County – one urban hub near the Covington riverfront and one suburban hub in Ft. Wright along Madison Pike. Service within Kenton County represents approximately 50 percent of TANK’s regional transit service while the other 50 percent of service is split between Boone and Campbell counties. TANK operates a total of 21 routes, 18 of these routes cross the river and connect to the Metro system in downtown Cincinnati. Aside from fixed route operations, TANK provides door-to-door service through the Regional Area Mobility Program (RAMP) for disabled citizens. TANK also offers senior transportation on a limited basis, available to senior citizens over age 67.

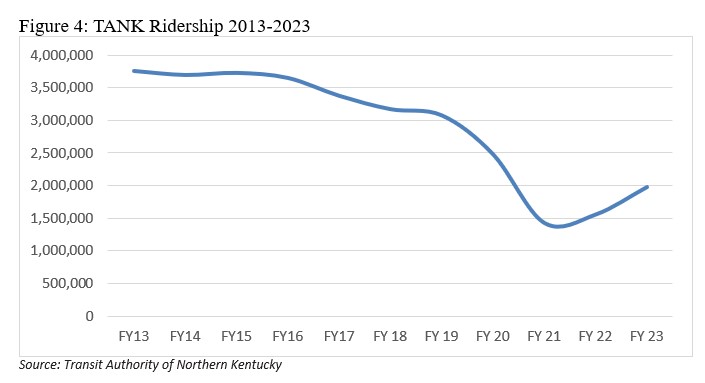

TANK serves the urban, first ring, and suburban sub areas of Kenton County through a hub and spoke route system as evidenced in Figure 3. From 2013-2023, total ridership on the system was 3 million riders per year until the pandemic. TANK saw the highest ridership in the last ten years during the 2013 fiscal year, with 3.76 million trips in Northern Kentucky. Figure 3 illustrates that transit routes primarily cross the county in a north to south orientation while east to west trips often require transfer at one of the transit hubs. TANK has attempted east to west routes in the past with limited success. In 2020, just before the pandemic closed many businesses, TANK rolled out a redesigned network, focused on frequency over coverage. Bus routes were focused on key corridors (Dixie Highway and Madison Ave/Pike in Kenton County) with more frequent, regular service. Routes with lower ridership were eliminated, allowing resources to focus primarily in these higher ridership areas. Bus routes in the rural parts of Kenton County were reduced – density in this area is currently too low to effectively support transit operations.

Lastly, it should be noted that TANK’s operations are dramatically affected by factors often outside of their control. Factors including gas prices, wage rates, not to mention pandemic/community regulations have an impact on transit ridership on their system. During the pandemic, TANK was deemed an essential service, as many essential workers (hospital, grocery, fast food, logistics) use transit to get to jobs. TANK plays this role in the local economy, ensuring that employers have access to employees – even those without personal transportation.

Tank saw a steep decline in ridership during the pandemic, as depicted in Figure 4. Prior to the pandemic, ridership had been slowly declining, reaching approximately 3 million trips in 2019. The low point in ridership was in 2021, with approximately 1.5 million trips. Since then, ridership has been increasing. It is still too early in the recovery from the pandemic to determine if ridership levels will continue to increase, and the long term impacts on transit service in Kenton County.1

Flight facilities refers to flight operations, either passenger or freight, originating from a specific geographic area. Air operations can be vital to a community’s access to the globe and can dramatically affect economic development within a region. Kenton County contains no publicly owned airports within its boundaries. The county does, however, operate the Kenton County Airport Board, which oversees the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport (CVG). The Airport Board sets the policies by which the airport is operated and implements strategies to ensure CVG remains a first-class facility for the region. This board is a key component of Kenton County and the overall region’s economic success as a thriving international airport helps drive business and the local economy.

Physically located approximately 1.5 miles to the west of Kenton County along I-275 in Boone County, CVG is a vital asset to the regional transportation network. In 2018, CVG activity supported more than 26,000 direct jobs and 48,000 total jobs within the Cincinnati MSA, more than $1.5 billion in direct labor income and more than $2.1 billion in total labor income, and nearly $3.9 billion in direct output and approximately $6.8 billion in total output in the Cincinnati MSA.2

Home to one of three DHL Express Global Super-Hubs and the first Amazon Air Hub, CVG growth is being fueled increasingly by air cargo. With a 41 percent increase, CVG was named the fastest growing airport for cargo traffic over the last decade (2008-2018). Moving more than 1.4 million tons in 2020, CVG’s status as a leading cargo airport has soared in international (#21), North American (#7), and U.S. (#6) rankings. (Sources: Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport (CVG). 2021. Airports Council International (ACI). 2019. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS). 2021.)3

Rail operations can provide a vibrant transportation option for residents in areas where it is available. This mode supplements other transit options and works to alleviate issues associated with congestion, delay, and emissions that are related to high single occupancy vehicle usage that is prevalent in Kenton County. There are currently, no passenger commuter rail facilities within the county, nor are any new facilities planned within the foreseeable future. The only passenger service that operates on a scheduled basis within the Greater Cincinnati region is the Cardinal line that operates out of Cincinnati’s Union Terminal. This route operates between New York and Chicago on Monday, Thursday and Saturday and stops in Cincinnati in the early morning hours.4

The most recent study of passenger rail took place in 2002 through a regional study called The Regional Rail Systems Plan, conducted by the Southwestern Ohio Regional Transit Authority (SORTA), TANK, and OKI. The study has never been implemented and is currently considered not to be fiscally constrained by OKI, meaning it cannot receive federal funding. The issue will be up for consideration when OKI updates the 2050 Metropolitan Transportation Plan, which is scheduled for adoption in June 2024.5

While passenger facilities do not currently exist, rail comprises an important part of the overall transportation network in the form of freight operations. 150.06 miles of railroad track are identified within the county on three main lines that traverse the county north to south. The OKI Executive Committee approved a Freight Plan on September 14, 2023. With 479 miles of track and 1,117 grade crossings in the OKI region, trains – after trucks – have the greatest freight presence in the OKI region. Two Class I railroads, CSX and Norfolk Southern (NS), operate within the OKI region. Sixty-four percent of all the rail miles in the region are operated by these two Class I railroads. Four short line or regional railroads operate within the OKI region; and they include the Indiana & Ohio Railway (IORY), Central Railroad of Indiana (CIND), Cincinnati Eastern Railroad (CET), and Indiana Eastern Railroad (IERR).

At both national and regional levels, the number one cause of rail-related deaths is railroad right-of-way trespassing. Between 2016 and 2020, the total number of our region’s trespassing injuries and deaths was double those that occurred at rail grade crossings. Of the 66 rail-related incidents over the five-year span, 73 percent of the crossings had a device to warn drivers, pedestrians, and bicyclists to oncoming trains.

About 137 trains travel on rail tracks in the OKI region daily. The greatest number of trains, more than 100 daily, travel through the heart of the region along CSX’s Cincinnati Terminal Subdivision track, between Mitchell Street, just north of CSX’s Queensgate Yard, and Longworth Hall, just south of NS’ Gest Street Yard. About 37 percent of trains are traveling at a maximum speed of only 10 mph, which is partially due to the number of rail grade crossings. Seventy percent of all crossings are rail grade with public or private roadways.

According to the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) Freight Analysis Framework data, in 2017, rail moved more than 7.5 million tons of freight valued at nearly $6.9 billion in our region. The Surface Transportation Board’s 2019 Carload Waybill Sample (CWS) data, for the Cincinnati Business Economic Area (BEA), shows that while the total rail tonnage has decreased by 14 percent since 2010, the revenue generated from this same rail freight has increased by 22 percent.

Rail grade crossings will continue to be a major concern within the OKI region, with the Freight Plan specifically recommending the at grade crossing on KY 236 (Stephenson Road) in Erlanger be eliminated.6

Kenton County experiences two physical boundaries (the Ohio River to the north and the Licking River to the east) that necessitate the use of bridges within the transportation network. To cross the Ohio River, bridges are concentrated in the urban sub area in Covington. Travel across the Licking River is via two bridges in Covington and farther south via the I-275 Bridge and KY-536 Bridge. There are seven vehicular bridges in Kenton County and three rail-only bridges for a total of ten river crossings. Aside from the KY-536 Bridge in the Visalia area and the I-275 Bridge in the suburban sub area, all bridges are located in the urban sub area.

Brent Spence Bridge

The Brent Spence Bridge carries I-71/75 traffic. This bridge is currently described as “functionally obsolete,” or built to standards that are not used today but still structurally safe for use. In 2012, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) approved a plan for a new companion bridge to address capacity and mobility issues.

This project is fully funded and advancing towards construction. The current anticipated project cost is $3.6 billion, which will be shared by Ohio and Kentucky. The cost of the companion bridge and updates to the existing bridge will be split 50/50 by Ohio and Kentucky, with each paying for the approach work occurring in their respective state. On December 29, 2022, Ohio and Kentucky were awarded federal funding grants totaling $1.635 billion from the Bipartisan Infrastructure & Jobs Investment Act for the Brent Spence Bridge Corridor Project, giving the green light to move toward construction.

Since 2022, the project team has been conducting neighborhood and public outreach meetings, selecting a design-build team, and finalizing the environmental assessment. Construction for the companion bridge is anticipated to begin in 2024 and last until 2030.7

KY 8 Licking River Bridge

The KY 8 Licking River Bridge is a critical connection for commuters, freight, pedestrians, and bicyclists traveling between Covington and Newport. Built in 1936, the current bridge has exceeded its original design life. With significant development occurring in Covington and Newport, a replacement bridge is necessary to support the growing needs of all travelers using the KY 8 Licking River Bridge crossing.

KYTC is in the process of designing and constructing a new bridge to replace the current bridge. They are currently selecting a final bridge design. Groundbreaking and a completion date will depend on which bridge type is selected.8

In addition to the bridge projects mentioned above, KYTC and local jurisdictions are pursuing other major projects in Kenton County.

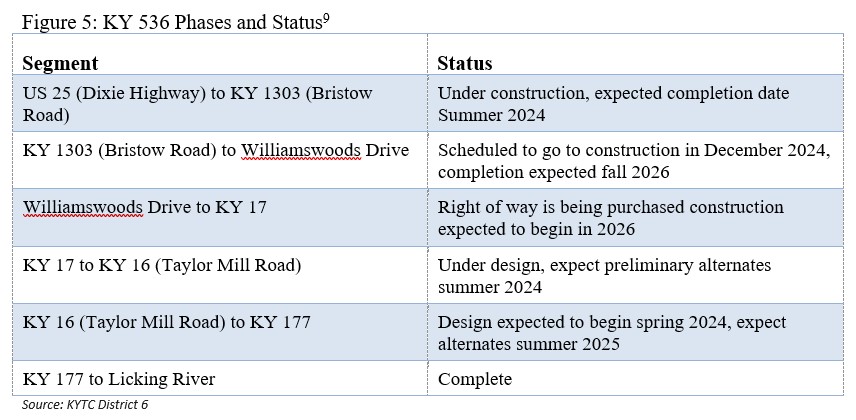

KY 536

KYTC is in the process of improving KY 536. The project is phased in multiple stages and sections. Figure 5 shows the current status of the different phases and sections of this project:

I-71/75 and I-275 Interchange

The I-71/75 and I-275 interchange is critically important to flow of traffic throughout Northern Kentucky and the tri-state region. The interchange serves thousands of residents, businesses and other commercial enterprises, and connects I-275 (which forms a bypass around Greater Cincinnati) with I-71 and I-75. Currently, the interchange carries more than twice the amount of vehicles per day than it was originally designed to manage, and traffic levels are expected to continue increasing as Northern Kentucky grows. This escalating traffic, coupled with challenging merges and highway entrance and exit patterns, has resulted in growing congestion and delays in the interchange area. Recent studies have confirmed what those who travel through the area already know: additional capacity and roadway improvements are needed.

KYTC launched the project in 2019, and as of November 2023 is in the preliminary engineering and environmental stage.10

Removal of the Scott Boulevard/Greenup Street KY 17 Couplet

In December 2023, the Covington Board of Commissioners voted to return Scott Boulevard and Greenup Streets to two-way traffic between 20th and 12th Streets. This evolution will also eventually involve moving the KY 17 designation west to Madison Avenue. The goal is to calm traffic, improve safety, expand walkability, and increase development in neighborhood business districts. This will result in the following changes:

Both Scott Boulevard and Greenup Streets will revert to two-way traffic from 20th Street to 12th Street. Currently, Scott Boulevard is one-way south and Greenup Street is one-way north their entire lengths. In 2022, KYTC updated its traffic counts and found that the average annual daily traffic for Scott Boulevard in that area was 4,462 vehicles. For Greenup Street, it was 5,494 vehicles.

Both streets will be resurfaced, as will Madison Avenue in the affected area.

New signage will designate Madison Avenue as KY 17 from 20th to 12th Streets.

To encourage traffic to slow down, traffic signals might become stop signs at some intersections.

Sidewalks will be rebuilt as needed at some intersections, with ADA ramps installed where they are missing.

Parking will not be affected.

The Kentucky General Assembly allocated $2.5 million for the project during the 2022 legislative session. The projected cost has risen to $3.66 million, due to mandated signal upgrades on Madison Avenue and state requirements for an on-site project monitor.

The goal is to have the entire project finished in 2024.11

The county’s physical landscape is made up of beautiful hills offering scenic views of the valleys below. This topography, while scenic, often limits connectivity because of gaps that naturally occur between the ridges. Bridging these valleys to connect roadways would be incredibly costly and is not a realistic option to increase connectivity. Increased connections are only realistic in areas where topographic constraints would not be cost prohibitive. Topography has also played a major role in directional mobility in the county. The next sub section discusses the county’s natural tendency to orient major travel routes in north/south configurations and examines the need for increased east/west mobility options.

Hills and valleys also pose tangible challenges to cyclists and pedestrians in the form of obstacles that must be traversed to get from point to point. The Urban sub area is predominantly flat and is located in the river valley. The First Ring Suburban area is also flat, although it lies on a natural plateau at higher elevations than the urban area. Both of these flatter areas lend themselves to increased chances for walking and bicycling as people choosing those modes do not have to constantly climb and descend hills of 400 feet or more. It should be noted, however, that limited connections in the network force cyclists and pedestrians onto main thoroughfares and limit options for secondary and tertiary route choices. Topography is a major constraint and should be considered as a real factor in mobility recommendations as the plan is drafted.

Kenton County has historically had reliable north to south mobility and has faced challenges when moving east to west connectivity. This trend remains evident in 2023 as well. Several routes traverse the county primarily in north to south alignments such as KY 16, KY 17, Turkeyfoot Road, US 25, US 42, US 127, and even I-71/75.

Conversely, the movement of people and goods east to west is accomplished on I-275 in the northern portion of the county, KY 536 near the county’s middle area, and KY 14 farther south in the county. I-275 was constructed in the 1970s and is a major interstate loop that traverses the landscape with less concern about terrain. Major cuts in the landscape, necessary to route the roadway, are visible alongside the roadway in the form of exposed rock faces. KY 536 carries traffic across the county, and is currently being improved and widened by KYTC. To a lesser extent, KY 14 moves east to west across a majority of the county in the far southern rural sub area of the county but it both begins and ends within the borders of the county. Even KY 536 and KY 14 tend to orient themselves with natural ridge and valley alignments and avoid constant topographic changes associated with straighter alignments experienced in newer roadways like I-275.

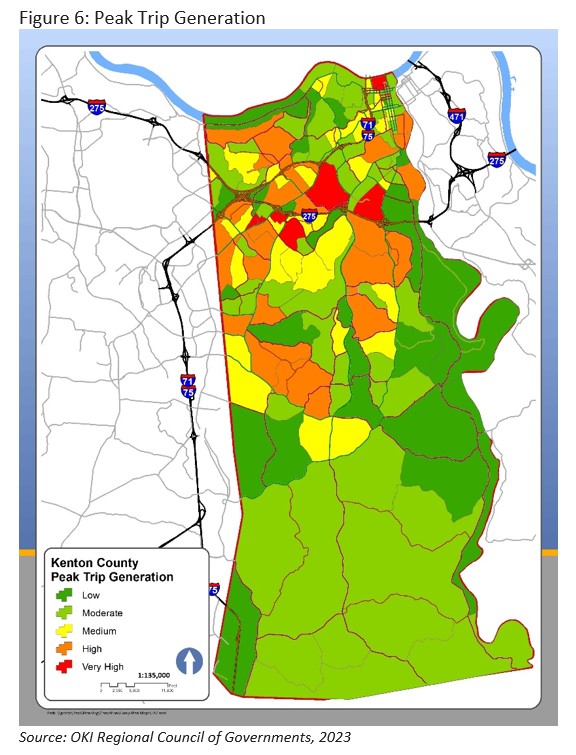

Traffic Analysis Zones (TAZ) are small geographic areas that help forecast future demand on the transportation network via OKI’s Travel Demand Model. These areas attempt to keep a similar number of people (either residents or employees) with homogeneous land uses. TAZs are defined by transportation barriers like major roads, rivers, or railroad tracks.

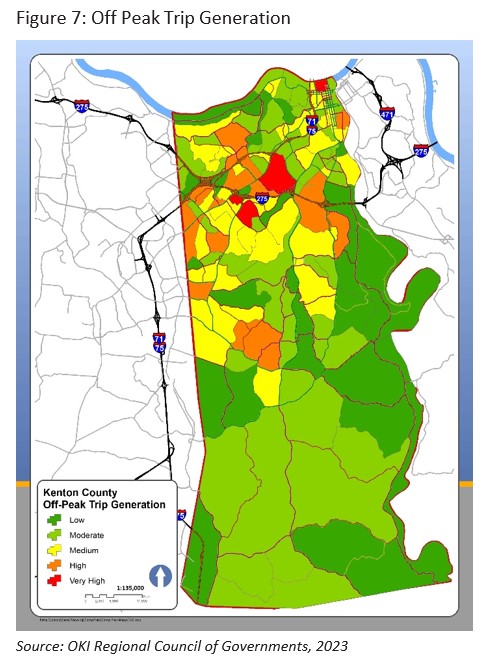

Examination of TAZs in Kenton County reveals some specific areas that experience high traffic volumes during both peak and off-peak travel times. Peak times generally include the hours of 6:30 to 9:00 a.m. and 3:30 to 6:30 p.m. whereas off-peak times encompass all other hours of the day. Figures 6 and 7 provides a visual representation of higher traffic volumes in specific zones throughout the county.

Assessing these maps indicates some of the following amenities are included amongst the highest trip generators in Kenton County for both peak and off-peak times:

- Independence Towne Center and residential areas in western Independence

- Manufacturing along Industrial Road

- Residential areas in Taylor Mill along KY 16

- Medical complexes in Crestview Hills

- Crestview Hills Town Center and residential areas immediately north

- Businesses and homes immediately south of the I-71/75 and I-275 interchange in Erlanger

- Residential areas in Crescent Springs and Villa Hills

- Residential areas in Park Hills between Dixie Highway and I-71/75

- The Austinburg area of Covington

- The Botany Hills area of Covington

- Covington central business district

The areas outlined in Figures 6 and 7 are important to note because they describe the most heavily utilized TAZs in Kenton County. Amenities inside these areas (whether work, residential, or retail) produce the highest traffic volumes in the county. Strengthening network connections between these nodes could be a strategy to help improve traffic flow in the county on a larger scale.

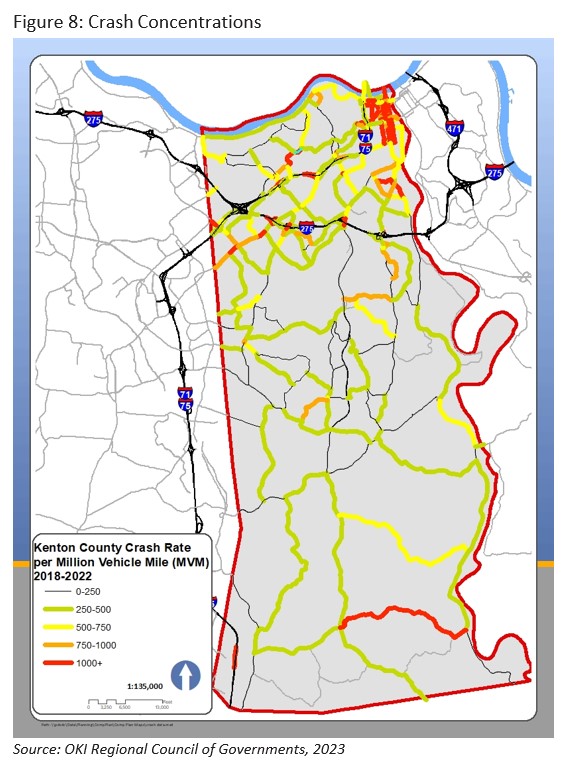

Analyzing crash concentrations is another way of reviewing parts of the transportation network that need to be addressed from a safety standpoint. Crash information is tracked by OKI on crashes per 100 million vehicle miles traveled (VMT) scale. Rates above 500 crashes per 100 million VMT are high by technical standards.

Figure 8 displays crash rates along major routes in Kenton County between 2018 and 2022. Some of the most dangerous non-interstate road segments for crashes are in the urban area. Segments of 3rd Street, 4th Street, Greenup Street, Madison Avenue, and 8th Street are all within the top ten segments for crashes.

Rural areas also experience some dangerous roads. The segment with the highest crash volumes in the rural area is Rich Road between KY 17 and Decoursey Pike in southern Kenton County. This segment experiences crashes per 100 million VMT, nearly twice as high the next highest roads, Decoursey Pike south of Ryland Heights and Kenton Station Road between KY 17 and Decoursey Pike.

While the highest concentrations of 100 million VMT crash rates are found in urban Kenton County they experience relatively low crash numbers compared to their average annual daily traffic (AADT) counts. For instance, 3rd Street between the Roebling Suspension Bridge and Scott Street has one of the highest crash rates per 100 million VMT, with 8,705 crashes per 100 million miles. This segment experienced 11 crashes between 2018 and 2022. The highest number of crashes in the county on non-interstate roads occurred on several segments of Dixie Highway, with over 200 crashes during this time period. 4th Street in Covington approaching the I-71/75 on ramp and Elm Street through Ludlow also experienced more than 200 crashes. While the number of specific crashes was higher, these segments do not rank as high as roads with higher crash rates due to their average annual daily traffic (AADT) counts. Normalizing these segments through the 100 million VMT metric indicates that while they have a greater number of crashes, they have fewer crashes per 100 million vehicle miles traveled.

The number of injuries and fatalities occurring on a segment also provides insight into problematic areas of the county. The highest number of injuries (65) was recorded on I-275 between the Dixie Highway and Turkeyfoot Road interchanges. I-275 east of the Turkeyfoot Road interchanges and Dixie Highway to the east of Boone County recorded over 50 injuries between 2018 and 2022. Three segments of roads have the county’s highest occurrence of fatalities. Two fatalities were recorded Pride Parkway north of the I-275 Interchange, I-71/75 north of the I-275 Interchange, and Dixie Highway at the southern end of the county. Thirty-nine other roadway segments experienced one fatality each and are dispersed throughout the county.

The Kenton County Transportation Plan is a comprehensive, multi-modal strategy for improving transportation in Kenton County. It includes a demonstration element for linking transportation improvements with the county’s future land use. The plan accounts for the importance of transportation in sustaining economic growth and enhancing the quality of life.12

After thorough study and discussion, the plan was adopted in June 2014. The end result is a list of 65 recommendations that are separated into high, medium, and low priority. The top third (22) recommendations are presented in detail due to their high priority status designation. It is noted that the remaining medium (22) and low (21) recommendations in this plan are also acknowledged as transportation needs for Kenton County. Figure 9 summarizes the plans recommendations.

Figure 9: Kenton County 2014 Transportation Plan Recommendations

Several projects are currently planned to improve vehicular traffic within Kenton County. Figure 10 show projects that are currently funded through the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) or recommended by the OKI 2050 Transportation Plan. TIP projects are those that currently have funding allocated through FY 2027. Projects listed in the 2050 plan do not have funding allocated at this time but could become active any time funding becomes available.

Figure 10: Kenton County Recommended and Programmed Roadway Projects

Mobility is comprised of a complex network of interconnected pieces that make up the overall system. Addressing the needs of all system users in the form of motorists, cyclists, pedestrians, transit users, aviation, and freight will require a comprehensive approach. This approach should be focused on actions that improve all parts of the network when an individual component is addressed. It should also examine how needs change across the unique sub areas within the county. The Comprehensive Plan, combined with the Kenton County Transportation Plan and Freight Plan will work towards exhaustively examining mobility needs in the county for years to come.

- Source: Douthat, G. (2023, December 1). General Manager – TANK. (Videkovich, A., Interviewer)

- Source: Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport. “About CVG Airport.” Accessed November 6, 2023. https://www.cvgairport.com/business/about/

- Source: Ohio-Kentucky-Indiana Regional Council of Governments (OKI). “OKI – Ohio-Kentucky-Indiana Regional Council of Governments Freight Plan.” Accessed November 8, 2023. https://freight.oki.org/.

- Source: Amtrak. “Amtrak – Train & Bus Tickets – National Railroad – USA & Canada.” Accessed November 8, 2023. https://www.amtrak.com/home.html.

- Source: Koehler, B. (2023, November 9). Deputy Executive Director – Ohio-Kentucky-Indiana Regional Council of Governments (OKI). (A. Videkovich, Interviewer)

- Source: Ohio-Kentucky-Indiana Regional Council of Governments (OKI). “OKI – Ohio-Kentucky-Indiana Regional Council of Governments Freight Plan.” Accessed November 8, 2023. https://freight.oki.org/.

- Source: Ohio Department of Transportation and Kentucky Transportation Cabinet. “Brent Spence Bridge Corridor.” Accessed November 9, 2023. https://brentspencebridgecorridor.com/.

- Source: Kentucky Transportation Cabinet. “Kentucky 8 Bridge.” Accessed November 9, 2023. https://www.ky8bridge.org/.

- Source: Videkovich, A. “KY 536 Project.” Email to Brefeld, L. November 16, 2023. Linzy.Brefeld@ky.gov. Forwarded by Brefeld, L., to Bezold, M., on November 16, 2023.

- Source: Kentucky Transportation Cabinet. “75275 Interchange Project.” Accessed February 13, 2024. https://www.75275interchange.org/.

- Source: City of Covington, Kentucky. “City Takes Step Toward Two-Way Traffic on Residential Areas of Scott, Greenup.” December 7, 2023. Accessed February 13, 2024. https://www.covingtonky.gov/news/2023/12/07/city-takes-step-toward-two-way-traffic-on-residential-areas-of-scott-greenup.

- Source: Ohio-Kentucky-Indiana Regional Council of Governments (OKI). “Kenton County Transportation Plan.” Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.oki.org/resource-library/studies-plans/kenton-county-transportation-plan/.